Update, May 21, 2023: I wrote this article back in 2020. At the time, Autodesk was a leader in generative design and was pitching it as the future of design software. After hearing this spiel one too many times, I penned this article critiquing their vision (as you can gather from the title, I wasn’t a fan). Fast forward three years and the generative design landscape is totally different. New tools like ChatGPT, Dall-E, and MidJourney have exploded in popularity, overtaking Autodesk as the leaders in this space, and leaving this article feeling a little dated (already!). In many ways, this article now serves as a strange time capsule – an old collection of issues with Autodesk's earlier version of generative design.

To bring this article up to date, I’ve added a short epilogue exploring what happened to generative design, why Autodesk’s strategy didn’t work, and reflecting on what I got right and wrong in the original article (spoiler alert: generative design didn’t die!)

A concerned Autodesk representative pulled me aside at an event recently. “I read your article,” she began.

I tried to recall whether I’d said anything controversial. But my most recent article was relatively tame, just 1,300 words in Architect Magazine about algorithms generating building layouts. If anything, it was complimentary of Autodesk.

Around us, people at the conference were discussing the industry’s most pressing issues – robots, automation, climate change. The representative leaned in to reveal hers: “I noticed you didn’t mention generative design in your article.”

The representative worked for Autodesk’s communications team. As you’ll be aware, Autodesk has been ramping up its efforts to brand and promote generative design, putting out a series of videos, articles, and presentations that tout the benefits of the generative process. Others in the industry have followed suit, announcing their own generative design tools in superlative laced press releases. None of this is new. People have been peddling generative design as far back as the 1980s. But it never had the clout of someone like Autodesk. After years of never really going anywhere, suddenly everyone is talking about generative design. Suddenly it feels inevitable.

The Autodesk representative seemed taken aback when I told her that I didn’t believe the hype. That I avoided using the term ‘generative design’ in the article because I didn’t think it was worth promoting. That it was a distraction. A white whale. That it wasn’t the future of design, or anything. That it was a dead-end. That something more significant was happening. That I needed more time to explain.

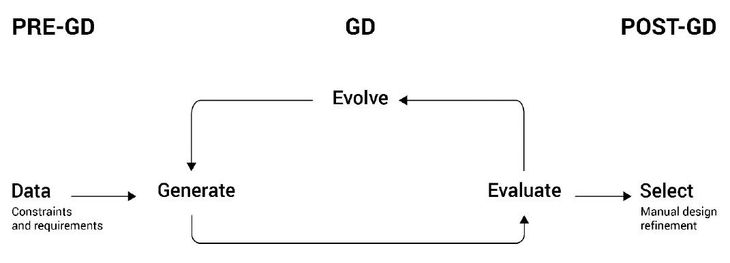

The three steps of generative design: specifying goals, generating solutions, and selecting the best option (source).

On the surface, generative design is an enticing vision. Rather than employing a designer to laboriously create a design concept, you can instead use an algorithm to quickly generate thousands of options and ask the designer to pick the best one. Effectively, the designer becomes an editor. They specify the goals of the project, an algorithm churns out an array of options, then the designer returns to select the strongest idea, and – voilà – you’ve got a building. Since the algorithm can produce countless design concepts, the designer can, in theory, consider more possibilities than they would on a typical project, improving the chances of finding an optimal design or discovering a novel solution. A better design with less effort, what’s not to like?

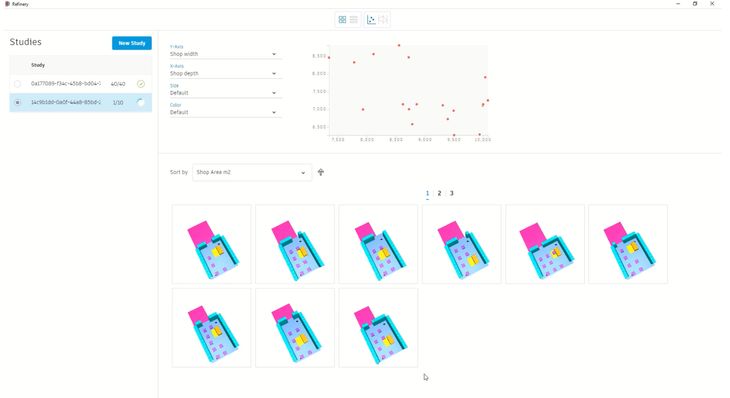

Comparing and selecting design options at the end of the generative design process using Autodesk's Project Refinery (source).

Some of you are going to disagree with how I’ve characterized generative design. In the current vernacular, the term ‘generative design’ has a reasonably loose meaning. This isn’t unusual — other technical terms like ‘parametric’ or ‘machine learning’ have grown more vague as they have become more popular. In the case of generative design, the word ‘generative’ is often confused as a catch-all for ‘generated’. Throughout this article, I’m going to refer to generative design as a three-stage process where (1) designers define the project’s goals, (2) algorithms produce a range of solutions, and (3) then designers pick the best result. Although you might quibble with this definition, this is how Autodesk defines generative design today, and it’s what many people are currently pushing as the future of design. For the purposes of this article, I’m only focused on this prevailing definition (if you think this process shouldn’t be called ‘generative design,’ if you’d rather call it optioneering or something else, you can change the name used in this article.

Whatever you want to call it, I’m deeply concerned that many in the industry are advocating that generative design is the future of architecture. As I’ll explain in this article, once you get beyond the marketing hype, there are real technical and human reasons why generative design’s three-step process is doomed to fail.

The Worst Way to Write an Email

To understand the absurdity of generative design, I think it helps to imagine generative design in a different context, to see it as a naked idea without the baggage of the architecture industry.

Consider email. According to McKinsey, the average worker spends about 11 hours a week reading and answering emails. Each email is hand-crafted, letter by letter, word by word. Clack, clack, clack. It’s easy to see why talented people hate doing this menial work.

So why not reinvent email? Rather than typing out each email, why not have an algorithm generate the first draft? Or a hundred first drafts? Why not make a generative email program? You pick the subject, an algorithm writes some options, you read them, choose the best, and hit send. Not only would you save time, but you’d also probably end up sending better emails because you can explore more possibilities and spend longer considering what you’re saying. What’s not to like?

All of this is technically possible. In fact, I’ve mocked up a quick prototype below.

GenerativeMail

GenerativeMail

Created with gpt2, gpt2 Cloud Run, and Paracord

Why Generative Design Doesn’t Work

I imagined that it’d be instructive to see generative design used in the most ridiculous way possible. But as I ran the generative email program for the first time, I was no longer sure if it was such an absurd concept. I mean, sure, most of the emails were incoherent, but every now and again one of them would be unexpectedly erudite. In those moments, you could see the potential. You could imagine that with better algorithms, an improved interface, and faster computers that this crazy idea might actually work.

Writing about generative design using generative design.

Generative design often appears close to working. It’s been that way for decades. Time and time again we’re strung along by seductive demonstrations and fooled into thinking we’re on the cusp of a breakthrough. These demos are easy enough to create. Take an algorithm that spits out hundreds of random designs, develop an interface to display them, combine, and you’ve got a passable mockup of generative design. Want to truly impress? Apply your prototype to a simplified design problem and explain that it’ll work just the same in a complicated, real-life situation. If there are any concerns about the quality of results, draw upon your inner techno-optimist to explain that the algorithm will improve with time. It’s that simple. It’s the sort of thing you can create in a weekend, on a lark, to illustrate a blog post.

While it’s trivial to show that generative design is possible, it’s much harder to take the next step and show that generative design is useful. In fact, it rarely happens. This is the real challenge of generative design: going from the plausible to the practical. Up until now, we’ve just been doing the easy bit, we’ve been showing that it’s possible. This feels like progress, yet the hard part is still to come. I don’t want to be a downer, but I don’t think we’ll get there. By my count, there are 6 major reasons why generative design is unlikely to progress.

1. You’re on the hook for generating the options

The way generative design is sold, it often appears that a designer only involved in defining the project’s goal and picking the best options. In reality, the designer is also responsible for creating the algorithm that generates the plans. Which is no small feat.

In the generative email program, the text is written by an algorithm called GPT-2. This program, developed by OpenAI, builds upon decades of research on neural networks and natural language processing. The result is an algorithm that can write everything from New Yorker articles to Harry Potter screenplays (GPT-2 was so convincing that OpenAI initially held it back, calling the software ‘too dangerous to release’ because of it’s ability to automate the production of fake content).

).](/img/Chair-Iterations-1024x648-1-dctFhLBmEd-730w.jpeg)

These chairs look similar because the underlying generative algorithm is limited in what it can produce. If you wanted to create a chair that looked different, you’d need to spend time rewriting the generative algorithm (source).

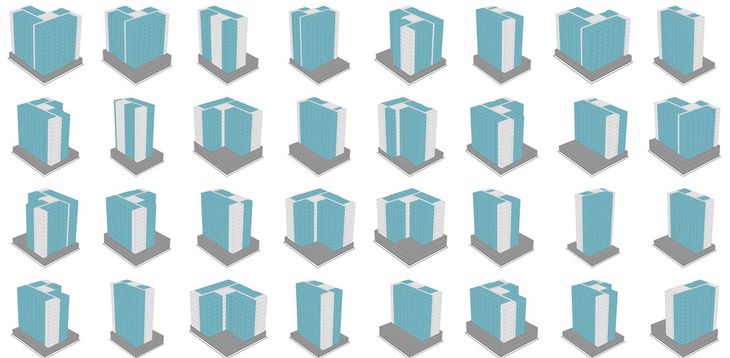

There is no GPT-2 for buildings. That is to say, if you’re using generative design, there is no pre-built mechanism for generating all the design options. Instead, you have to create your own system. From scratch. This is a bit like creating a factory that manufactures design schemes. If the factory is repetitively making a reasonably uniform product, then it’s relatively straightforward to setup. But if you want to produce a lot of variation, then it can get really complicated. In many cases, it will take more time and skill to set up the factory compared to doing the work manually. To avoid this complexity, people tend to limit what the factory can produce, which is why demonstrations of generative design often churn out hundreds of similar-looking design options. Rather than exploring the full range of design outcomes, you end up exploring what the algorithm can create. Often this produces less exciting outcomes and takes longer than you’ve been led to believe.

2. Quantity doesn’t substitute for quality

If your boss asks you to sketch out a proposal, what is the right number of plans to produce? Perhaps you’d return with 3 to 5 ideas. If you’re feeling confident, you might advance just a single proposal. But you’d never, in any situation, come to your boss with a presentation containing 100 different schemes. It’d be absurd.

Yet, with generative design, we routinely generate hundreds of different options. And we celebrate this like it’s a virtue. The thinking is simple: the algorithms can’t tell good ideas from bad, but they can create designs incredibly quickly, so if we rapidly produce hundreds of options, we increase the chances of inadvertently generating a good design. Effectively, we buy more lottery tickets.

The deluge of options obscures the fact that most of the outcomes aren’t viable. In the case of the generative email program, if the algorithm was any good, it’d be able to select the 3 to 5 most compelling drafts. If it was really confident, it’d select just one. But instead, we have algorithms that thoughtlessly create hundreds of options. This isn’t a virtue, it’s not the future, it’s a byproduct of lousy software. The fact of the matter is: one hundred shitty designs aren’t anywhere equivalent to one considered design. If your software was any good, it’d produce fewer designs, not more.

3. Comparing options is harder than it looks

Design options from Parafin (source).

Once you’ve generated all of these options, a person needs to select the best proposal. This is one of the main appeals of generative design – the algorithm handles the laborious work of creating the options, and all you have to do is sit back and pick your favorite.

It sounds leisurely, but it is actually difficult work. Ask any professor: would you rather grade 100 student essays or write one article of your own? Truth is, it takes effort to consider a design option seriously. And the challenge of evaluating different options only increases as the output becomes more involved and more complex. For example, 100 emails can be skimmed relatively quickly, but 100 books would require a lot of reading. Now imagine comparing 100 different buildings, I mean really comparing them, not just skimming through the images – oy vey!

Further complicating things, humans hate having too many choices. More choices give us more opportunities to make the wrong decision (which is something we fear), and the choices make it cognitively challenging to recall options and draw comparisons. This is sometimes called ‘overchoice’ or ‘the paradox of choice.’ Research shows that we particularly dislike being given a lot of similar alternatives, as is often the case for generative design, since there is no clear winner, leaving us to make a seemingly impossible choice between nearly identical options.

To put it simply, presenting designers with a lot of options is generally a terrible idea. Designers will find it stressful, they’ll struggle to make meaningful evaluations and comparisons, and it might not save as much time as you’d expect because it’s such an involved process to do well.

4. What you can measure isn’t what matters

Proponents of generative design argue that having too many options isn’t a problem because you can always hide the bad ones. You just need to measure the performance of each option and remove anything that doesn’t match the designer’s performance criteria.

In the generative email program, you can filter the emails by length. Admittedly, the length isn’t the best performance metric, but it’s easy to calculate. Perhaps in the future, we’ll be able to measure more critical factors, like the text’s persuasiveness or wittiness. But it’s not guaranteed that we’ll get there. Just because you can count the number of words in an email, doesn’t mean that one day you’ll be able to measure these more visceral concepts.

In the field of architecture, there’s no consensus on what constitutes good architecture and no established ways of measuring it. So we measure something else. In the 1960s and 70s, a lot of research focused on evaluating buildings in terms of walking times between rooms, which was easily calculated but not particularly important. Today, we might look at solar gain or view analysis, which is a component of architectural performance but not the full story. Perhaps in the future, we’ll be able to quantify other more visceral aspects of architectural performance, but I’m not holding my breath.

For people using generative design, this puts them in a bind. They can either use these arbitrary metrics and end up optimizing for the wrong thing, the thing that can be easily measured. Or they can ignore the metrics and wade through a lot of unfiltered options. I don’t see this situation improving any time soon – architectural performance is so complicated that we may never get to a place where we can quantify it and use it as a filter.

).](/img/6a00d83452464869e2022ad379b270200c-g6P-ouBg3l-730w.jpeg)

Apartment layouts are compared using solar potential, revenue, and program, which are easily calculated measures of performance but not the full picture. It is easy to inadvertently optimize for the calculable rather than the important (source).

5. Designers don’t work like this

Generative design simplifies the design process into three steps: briefing, ideation, and deciding. This is a gross simplification of what architects actually do. It feels like a caricature cooked up to tease designers, ‘oh, you know those melodramatic architects, all they have to do is take the brief, create a bunch of options, and pick their favorite, what’s so hard about that?’ Honestly, it’s insulting.

Study after study has shown that designers don’t follow a linear process, that design is necessarily messy and iterative. You experience this writing emails. You’ll write something down, re-read it, realize it sounds wrong, revise, re-read, edit, and iteratively work towards a final draft. At WeWork, Andrew Heumann recorded architects as they worked, and observed a similar pattern as he watched designers rapidly cycle between macro and micro changes, between the broader project objectives and the specific implementation.

In demonstrations of generative design, the iterative nature of the design process isn’t apparent because there are no real stakes. You don’t have the pressure of design reviews, the insanity of client revisions, budget cuts, and public submissions. You’re playing a designer on easy mode.

On a real project, you’ll never get it right the first time – the generative design algorithms aren’t good enough, and the circumstances of the project will change once you’ve created your first draft. So you have to make revisions. And generative design doesn’t accommodate revisions since it assumes the design process only moves forward. To make a revision, you either need to throw everything out and start the generative design process again, or you can abandon using generative design and make the change manually. Either way, generative design makes it hard for designers to work iteratively.

6. No one else works like this

The most damming indictment of generative design is that you don’t see it used in other creative fields. Adobe isn’t holding press conferences saying that generative design is the future of graphic design (InDesign will just be an interface where you upload your text, the software creates 100 different page layouts, and the designer picks their favorite). Apple isn’t pushing generative design for Final Cut (upload your raw footage, the software edits 100 different films, you watch them all, and pick your favorite). Microsoft isn’t adding generative design to Word. Autodesk isn’t even hawking generative design to their other key markets, such as media and entertainment.

To be fair, some things on the market today that resemble generative design. Spotify, for instance, will automatically generate several playlists and let you pick your favorite to listen to. But Spotify has an advantage, they can build this once and sell it to millions of customers, they’re not creating a one-off algorithm to redesign their office. Additionally, the interface is quite different to what we’ve been calling generative design - you don’t give Spotify a brief, and the software only produces a handful of carefully curated options (it’s not randomly putting songs into hundreds of different playlists).

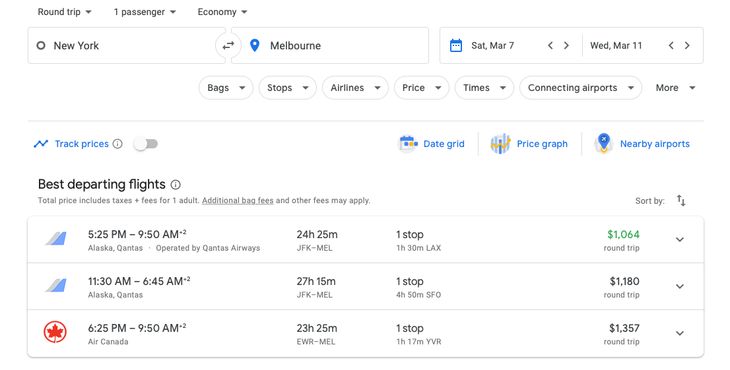

Flight booking websites essentially follow a generative process, you enter the brief (dates and destination), it creates dozens of itineraries, and you select the best combination. But is it the future of design?

The only place that I’ve really seen generative design thrive is on flight booking websites. These websites essentially take you through a generative process: 1) you specify the dates and destination, 2) the software generates dozens of different itineraries, 3) and you filter the routes by time, cost, and stopovers, and then select the best one. It works well. But anyone that’s used Google Flights and thought that it’d make a good design interface is out of their fucking mind.

If not generative design?

Generative design is our industry’s white whale. We’ve spent years hunting it with money, PowerPoint slides, and armies of interns. You get the sense that we’re within striking distance, and yet we’ve never landed it. It feels like we’ve made progress, and yet there are seemingly insurmountable challenges ahead. It feels possible, and yet never quite practical.

My concern is that many companies have jumped on the generative design bandwagon, swept up in the mania, never pausing to consider why this hasn’t worked previously or why other design industries aren’t onboard.

A lot of this would be avoidable if we had a better understanding of how design actually gets done inside architecture firms. Truth is, we know shockingly little about how design happens – especially in a digital world. As a result, people end up prophesizing about the future of the design, based not on an understanding of the design process, but on an understanding of the technology. Often this comes with fairly naive and condescending assumptions about the work that designers do, which makes concepts like generative design seem reasonable, perhaps even desirable.

Until we get to a point where algorithms replace designers (which may never happen), algorithms will only be practical if they work with humans. The real challenge isn’t the technology, it’s the interface, it’s how the algorithms fit the designer and their process. Generative design asks designers to change this process, to follow a stilted three-stage procedure.

To me, a more fruitful path seems to be taking the existing process and finding ways to enhance it with algorithmic smarts. Consider email. The process is similar to typing a letter on a typewriter, except you’re surrounded by spell-checkers, predictive keyboards, smart compose functions, bots, spam filters, and email prioritizers that all work alongside you, assisting, guiding, and bettering your writing. Creators of other design tools, such as Adobe, have gone in a similar direction, developing algorithms that work within existing design processes. In Photoshop, for instance, Adobe has developed targeted tools that automate specific procedures (such as content-aware fill and smart object selection). The designer works in a familiar manner, but computation is helping accelerate tedious tasks and guiding the user through challenging decisions.

In the end, I get the appeal of generative design. It’s alluring, captivating, and perhaps even inspiring. But generative design’s problems with choice overload, imprecise metrics, and a lack of design integration are so core to how it operates that they’re probably insurmountable. Or at least not easily solved by the usual trio of proposed solutions: better algorithms, an improved interface, and faster computers. Ultimately, I worry that generative design has become a distraction. I’m left wondering what might have happened if we were guided by the process instead of the technology.

I’d like to thank Andrew Heumann and Nathan Miller for their thoughts and comments on an earlier draft of this article. I’d also like to apologize to all my friends working on generative design applications – I love you all.

SEC Disclosure: I own a small amount of Autodesk stock because ultimately I have more faith in Autodesk's marketing team than any of the arguments in this post. Nothing in this article should be taken as investment advice.

Epilogue

May 21, 2023

This article is an interesting snapshot in time. I wrote it in February 2020, a few weeks before the pandemic shut down everything. And while that was only three years ago, a lot has changed since then, especially when it comes to generative design.

Back in 2020, generative design was poorly defined and not widely used. Autodesk was leading the conversation. They had latched onto the term and were using it to describe their vision for the future of design. In this world, designers would function more like curators, picking from hundreds of options that computers created.

In retrospect, Autodesk’s vision of generative design seems pretty prescient. But despite their early advantage, Autodesk isn’t a major player in generative design today – companies like Microsoft, Google, and Adobe are far ahead. So what happened?

A critical clue lies in the differences between today’s generative design tools and Autodesk’s vision three years ago. Autodesk imagined generative design being this three-step process. First, a designer would create a parametric model, then a computer would churn through different permutations of the model, and finally, the designer would sort through all the options and pick their favorite.

This process is actually quite different to how tools like ChatGPT function. For one thing, you don’t have to create the underlying model. OpenAI has already developed a large, general-purpose model (the GPT of ChatGPT) capable of doing everything from writing songs to composing college essays. But as I point out in the article, there isn’t a general-purpose algorithm for architecture, so “you’re on the hook for generating the options.” This is one reason why ChatGPT feels easy to use – all the hard work of creating the model is already done. But in Autodesk’s version of generative design, this is a task a designer has to undertake on every project.

Another key difference is that most modern generative design tools only produce a couple of answers. Midjourney generates four different options in response to a prompt. ChatGPT produces one. But Autodesk was fixated on giving designers lots of options. For them, the big challenge was generating and sorting these options efficiently. Most of their resources went into solving this problem. But it turns out, this was the wrong problem to solve because you don't always need to generate lots of options. (“If your software was any good, it’d produce fewer designs, not more.”)

So while Autodesk was messing around with ways to generate and sort hundreds of design options, the other companies were inventing these powerful, general-purpose models (like GPT). And ultimately these versatile algorithms that could be applied to any project proved more productive than developing an interface to create a bespoke algorithm for every project.

At the moment, generative AI is at a really interesting stage. While the underlying technology continues to improve, much of the innovation from companies like Google and Microsoft centers around the interface. It's a critical detail (“the real challenge isn’t the technology, it’s the interface, it’s how the algorithms fit the designer and their process.") Even for something like ChatGPT, the underlying technology has been around for a while. When I wrote the article, I used GPT2 for the email tool, which is a slightly earlier version of the language model that ChatGPT uses. So the technology was out there. People were building things with it. But it wasn’t until OpenAI hit upon the chat interface that it really took off.

I’m still skeptical about whether we can create a GPT for architecture. The main problem is the data. Tools like Dall-E or GPT require huge data sets to train. But in architecture, there isn’t a large corpus of models to train an algorithm on. Autodesk certainly has the potential to gather this data (and in some alternate reality, they spent time getting this data rather than going down the rabbit hole of creating interfaces to sort design options). But even if a GPT for architecture is never created, these other tools will still have an enormous influence on the architecture industry. Just look at the amount of writing most architecture firms do – whether it’s sending emails to clients or responding to RFPs. Much of this work will be automated by these new tools.

So whatever the case, these generative algorithms are coming for the architecture profession. I think we can pretty confidently say that generative design isn’t doomed to fail. But it has shifted and changed over the past couple of years. Generative design today is different to how Autodesk imagined it. Looking back on this article, it feels like a review of a Nokia phone in 2006 – it’s kinda moot when the iPhone gets released a year later.

Sayjel

Hi Daniel - We met at a conference a few years back. Totally agree with the premise of your article. Just wanted to share with you the work my startup is developing which focusing on a more natural human interfaces to algorithmic design. Curious to hear what you think. Here is a recent blog post I wrote about our thinking:

https://medium.com/@sayjelpatel/augmented-intelligence-for-sustainable-design-and-architecture-2f96a2fac95e?source=friends_link&sk=8d4917c8d78fbf24adfd04ca1d23fb31

Daniel Davis

Hey Sayjel, I really like where you're going with the augmented design tools. From my perspective, what you're working on looks pretty slick, particularly how the designer can go back and draw changes while the algorithm works around them. But I think the real test will be how urban planners use the tool and whether it makes sense with their process. I'm looking forward to following your progress!

Yongjoon Kim

Thanks for this great article! So much resonance in this argument. I've been into this 'generative design' or 'automated layout' approach, but ended up finding that it has a risk to undermine our creative field. What needs to be automated is those trivial, tedious, and repetitive tasks, not the massing or layout which is THE most critical part of the architectural design. It reminds me of one of my school projects: A dumb algorithm that generates hundreds of 'Bjarke-esque' massing and see how we can develop the design in reverse-engineering. And I ended up realizing that what adds a huge value to architecture is those painful and mentally exhausting processes during a design decision making, in which we reveal our true creativity as a human being. (And that's when we grow as an architect I believe!)

Ironically, this is why I still think that generative design(or whatever it is called) has a potential, while some architects are worried that it will take their jobs. I think it's opposite. Technologists and designers can work together and determine which parts of a design process is the biggest waste of time, automate it, and give the time back to the designers such that they can use those times for more sophisticated and meticulous decision makings.

Kris Weeks

Daniel, this is a really thoughtful article. I've had similar thoughts but have not articulated them nearly so clearly or thoughtfully as you have. Thank you.

Kai

I feel like I am out of the loop... isn't Autodesk's "generative design" just an evolutionary algorithm? I don't really understand why it's getting so much hype. I thought it was obvious that it would only really be useful for design problems which have very clear criteria for success and multiple competing variables. Hence why the best use cases are within an engineering context; more of an optimising process than a "generative" one.

If Autodesk thinks that generative design will be the next big thing for architecture, to use your own words they are out of their fucking mind. Design and especially architectural design is an inherently wicked problem and a practice driven by theory. Until we get general artificial intelligence, I don't see algorithms designing buildings on their own.

I enjoy reading these articles, please keep it up. I feel like there is not enough thoughtful critique and theorising of how technology continues to impact architecture.

Regards,

Kai

ralphg820

Autodesk also has generative design for Fusion 360 in its mechanical CAD division, but for Inventor users it is very awkward to access.

Gpt2

Hi Daniel,

Generative Design was my first post, and I know all your readers from your blog. It is really nice to read your blog again, and to say that you like my blog. For the past year or so, I have been writing a lot about the power of design in the application industry, and I always come across a lot of interesting ways to achieve great results. I hope I will be able to contribute to your post in a timely fashion, as I hope you will also be willing to share your thoughts. Also, I also want to share with you my thoughts on the direction of the development process in the design industry.

Warm wishes,

Gpt2

Chris Wilkes

Hi Daniel, Thank you for writing this article. I differ with your opinion of Generative Design, but understand the argument you made. If GD is being evaluated only in architectural cases and the only GD solution studied is Autodesk then your conclusion is spot on. The line that best summaries the problem comes from you as "To put it simply, presenting designers with a lot of options is generally a terrible idea."

But in the mechanical engineering world, we use GD frequently. And we use software that limits the design options based on specific criteria so the user is not flooded with an extensive array of ideas. AI (limited) is used to narrow the options. Our definition of GD comes from an recent paper by the ASSESS Initiative and says:

"“Generative design is the use of algorithmic methods to generate feasible designs or outcomes from a set of performance objectives, performance constraints, and design space for specified use cases. Performance objectives and constraints may include factors from multiple areas including operational performance, weight/mass, manufacturing, assembly or construction, usability, aesthetics, ergonomics, and cost.”

A detailed explanation of Generative Design for our field is here: https://enginsoftusa.com/what-is-generative-design.html.

The Altair Inspire software is a good example of how intelligence is added into the GD process.

The software you reference does little to provide intelligence to the process of choosing an optimal design. But with improved intelligence, GD can provide creative ideas to solve some very complex design challenges. In particular, when we add constraints around how a part will be manufactured, software can show us only those designs that can actually be built by that method. For example, subtractive manufacturing can only build certain designs and 3D printing can to others.

With improvements in the intelligence in the software, it is certainly possible that GD will have better utility in your field as well.

Daniel Davis

Hey Chris,

Thanks for sharing your perspective of using generative design outside the field of architecture. I’ve got to admit I have a fairly heavy bias towards architecture and I was really trying to push back against this idea that generative design is likely to be a prominent part of the architectural design process. That said, I can see how generative design would function in situations where the constraints are known, the performance criteria is easy to define, and the underlying algorithm for generating the options can generalize across many similar problems. It’ll be interesting to see how much further this can be pushed in for mechanical engineering.

Daniel

Sean

Thank you for writing this. As someone who has part of a design "automation" push at multiple offices, having to go through these exercises is time-consuming and pointless. We invariably make a tool specifically for 1 project, and try to make it as universally usable as possible, but some variable is always different, needing updates to the definition/script, new variables to evaluate the options by, etc. My fear is that this isn't 'doomed to fail' completely. My fear is that developers and builders co-op this the same way they've co-opted minimalism and modernism. A race to the bottom of the design barrel, where the only consideration is cost, and the quality of the building is never thought about. I think that's where this technology will wind up living. An algorithm that takes into efficiency and cost inputs will be used, and the option that maximizes those will be picked, damn everything else. Maybe I'm wrong, but that's where I see the future of "generative design" going.

Daniel Davis

I really hope it doesn't go that way. From my point of view, it seems that there is still a lot of room to experiment with different interfaces for embedding computation within the design process. Even with Autodesk sucking up a lot of the oxygen, I look at things like UpCodes or TestFit and it gives me hope that people are going to find better ways of doing this.

Marcelo Bernal

Thank you for refreshing the discussion around this topic. Before discrediting the efforts of an entire community of researchers, I think there is a deeper conversation regarding when GD along the design process can effectively contribute, the different techniques to generate design populations (brute force, stochastic, or statistical sampling), data visualization and analytics, methods for decision making, or the evolution of the design culture itself (which if highly unstructured). If you are criticizing ADSK, agreed. They totally miss the point, but mainly because of managerial decisions, not because of the quality of the research team. On the other hand, at the corporate research level, I have seen specifically in the Advancing Computational Building Design conference many examples of successful implementations in schematic design stage ranging from open ended apparently creative process to very narrow design space explorations. In my experience, yes, designers get overwhelmed in the beginning when I present 2000 variation, however once they see the power of data analytics, for example sensitivity analysis, they just love it.IN fact, they have learn how to use the data to better communicate with clients. In addition, we cannot disregard an entire generation of computational designers currently in college that will be influencing the practice. Let's talk in five years from now.

Dan Peel

Daniel, Thanks for the article - i think its really important to show both sides of an argument.

I agree with the points you make (and you make them well!) but they don't lead me to the conclusion that 'generative design is doomed to fail'. Instead i think they highlight the importance of choosing the right tool for the job - which is true of any tool. "It is easy to inadvertently optimize for the calculable rather than the important" - how true - but the onus is on the user to apply the tool to an optimization problem where a wide range of solutions can be readily parameterised and success criteria can be sensibly quantified.

Generative design is certainly not a panacea for all ills but it is an incredibly powerful tool in the right situation.

Reg Prentice

I suspect GD will be successful in proportion to the amount that is known about the end result before design is started. To look at the extremes: If all aesthetic directions, materials, and construction methods are on the table, the percent of useful solutions generated might be close to zero. But if it was known that the finished building would be constructed from a limited number of standardized modular units, the percent of useful solutions might be high.

Betsy

Very interesting writeup! From a less creative designer perspective and more mechanical analysis -- in industries like aerospace, Generative Design is used for weight reduction. For mechanical analysis these programs are used for weight-critical components, generating the new shapes, and then perform further (more accurate) analysis in other programs, and then do physical testing. The GD output isn't usually the final result, but it can be very eye-opening to see where weight and material can be reduced in a part and use it as a starting point for further analysis. I will add that one must be skilled in FEA to even start the process. Autodesk simplifies this and therefore the program makes analysis look easy -- it's not. But it's a fun starting point, a cool feature, but nobody in critical-design industry would use it at this point. Altair HyperWorks is used in industry. However, Autodesk provides it at such a low cost, giving the opportunity to try out advanced analysis techniques for students or less-critical design projects.

Will Walker

I think your interpretation of the generative design process is naive.

I also think when most "hard" designers (architects, design engineers, industrial designers, automotive designers) refer to generative design, they neglect important parts of the machine learning side and the user experience side.

If you speak to ML folks, the real limitation of the process is getting good data labeling to the algorithm, I.E. what makes a "good" or "successful" design. There's no feedback loop for an adversarial algorithm to be applied to this process which would automate the "editor" step in your model. It's really the advances being made in adversarial machine learning that have provided the jawdropping advances in outcomes we've seen over the past few years (alpha zero etc.).

As an interaction designer, I also think that the "hard" design fields of architecture and industrial design are woefully neglectful in gathering naive user feedback with simple prototypes. By the time they field a device and identify user failure modes, the molds have already been cut and the tools have been made. A weakness in most generative design models I have seen is that they make no accounting for user input or testing as part of the design process.

Louis Larosiliere

Will, I completely agree with your comment concerning the cursory interpretation of the generative design process and it's practice by so called "hard" designers. Advances in AI, including Machine Learning invalidates most of Mr. Davis' negative comments...

David

Hey Daniel, are you aware, this article comes up in like top 10 results when people look up "generative design"? That's how I found it. I'm really curious about that "something more significant was happening" part you mentioned at the beginning. I feel the same way, but can't quite piece it all together. What do you think might that be? I'm doing some reading on big data companies, knowledge economies, insights and decision making and feel like that is where this should be heading, especially in design. All I want are clear insights, to make (better) decisions. Focus should be on sustainable design, how much money, how much time, how much CO2 and how to make it less. Surely that can be done.

Daniel Davis

Hi David,

What I was hinting at is that I feel there are some large changes underway in how algorithms, designers, and decision-making systems work together. For the past decade or so, the focus has been on a lot of these project-specific, single-use tools like parametric models and scripts. But in the last couple of years we've seen things like Testfit and Upcodes approach computational design in a different manner, generalizing the algorithms to work in a different context and building businesses around them. It seems inevitable that we'll get to better decision making like you describe. But I think there's still a question about the best way to deliver that insight to designers. To me, generative design feels like the wrong interface, a less promising path in a much bigger change the industry is experiencing.

Santiago

Thanks for your article Daniel. I'd like to see a team that has been investigating on GD pivot in new directions.

Although GD has not been useful to me personally as a designer (in architecture) in the past, the individual pieces that GD is built from (i.e. design abstraction, requirements analysis, 3rd party analysis automation, etc) do strike as being potentially useful.

I would suggest a follow-up activity with open participation from the design community, on which ways design technology could go next. (This probably is already happening, and I'm oblivious because I live under a rock).

I notice in industry colleagues a fascination for some of the constituent parts of GD. If they were used together differently, could we arrive to a technology that is indeed useful to designers and aligns well with design process?

Ramon Lorenz

Regarding politics of the last 2000 years or so... things being doomed to fail won’t stop people from pursuing them with all possible dedication.

jl

Talk about coincidences (there are none). I just posted this in another website an hour ago, and then i found this site:

"Since my school days i have always wanted to be able to draw and model something and then generate iterations of this model by changing some parameters. Of course, we have always done this, either by hand or in computer 3d models, but never in an automatic, parameter controlled ways. The late architect, and in my opinion, a genius, Enric Miralles, once described his process like this: he drew something and the made hundreds of variations of the same thing, by hand, before passing his idea to someone else to put it in the computer."

It is that spark of human creativity that still hasnt been captured, and i dont know if it ever will, but i think we certainly can input it and the use generative design as an aid to take the idea to its ultimate consequences.

The library of Babel in Jorge Luis Borges short story contained an incredibly big number of books, each different from each other by one letter. Most of them where full of incomprehensible letters, but every once in a while you could find meaning in there. Everything that could ever be said was written in one of the books.

I once dream of a form "that contained all the forms" (it had a voice of its own). And the forms were affected by what you thought. Sadly i woke up before i could see a specific form manifest itself

nickhockings

This article, or something very close to it, applies to much of the recent promises of artificial intelligence. They commonly massively underestimate what it is that a human must learn in order to become competent in whatever task it is proposed to automate. Creating a broadly useful artificial general intelligence is certainly possible, but it is nowhere near as trivial as the current hype presumes. Current AI systems lack depth of understanding and the ability to learn from minimal examples.

Thank you for pushing back and presenting a clear argument against marketing nonsense.

Daniel Davis

Your point about AI is really salient. It's a similar situation where people have been able to show success in narrowly defined problems, which we assume will scale to something larger, but it never quite happens like that in reality.

vijay

very Thoughtful article Daniel,

if we look at some of generative design solutions mainly in space planning for architecture, there so much similarity among proposed designs, now many are pushing wind-solar analysis as main selling points of project and as you have said correctly At present its an white whale, look at some of recent insane amount acquisitions by leading BIM companies.

Another question remains, if one makes an decision based on tools suggestion, construction being investment intensive and long duration from planning to actual construction, who will be held responsible if those suggested assumptions result in major flaws with rework to losses.

m-sterspace

Great article. I think points 2 & 3 are a little weaker in that I think that generative algorithms could start improving by producing fewer better options by filtering out the similar but worse scoring ones, and that when it comes to concrete metrics that are easy to measure (which is what the algorithms are based on), there's a number of different techniques for multi variable analysis, from parametric line charts to machine learning dimension reduction / clustering algorithms that are commonly used in other fields like biology. I don't think that either of these points are real show stoppers for generative design.

That being said, I view points 4, 5, & 6 as the real and complete show stoppers that even if they don't make generative design dead in the water, will at least prevent it's widespread adoption for decades upon decades. There aren't any generative algorithms that are designed to be run more than once, or to have tweaks made to them after the fact. That means you either need the ability to fully generate a building, and all of its documentation, from an algorithm, or you can only run it once and pick it and then still have to do a ton of manual design and adjustment which limits generative design to basically exclusively early stage design, or things like facade panels that have no impact on the rest of the building.

There's a lot of people in the industry who have fully bought the marketing on this one, it's nice to see some rationality cut through.

Nathan Higgins

Hello! I thought this was great. I wonder, though, if generative design might work for buildings that are a little more basic. I'm thinking salt sheds or maintenance buildings that cities own. They tend to be cheap and probably not highly designed now. What are your thoughts on whether generative design might help improve the design of those buildings?

Daniel Davis

Hey Nathan, I think you're right that simpler building typologies lend themselves to automation. The question is, what's the best interface for creating those designs? In many cases, a simple parametric model might suffice. If I look at a tool like Testfit.io, which produces far more sophisticated buildings, their software functions much more like a parametric model than generative design – they're not presenting users with thousands of options to pick, they're generating the best option from a set of parameters. So I think you'll see automation like this, but I don't believe generative design will be the interface to that automation.

Dexter Reyes

I started this article with an open mind and willing to hear some genuine pitfalls of GD (generative design). In fact the author starts the article with what sounds like a fair assessment of what GD is, but as soon as they jump into their argument, it seems like they actually don't know what they're talking about.

For example the author uses generative email as an out of context example of why GD doesnt work. First of all, you don't DESIGN emails, you narrate them. It's a method of communication. This isnt a well thought out example at all and yet the author routinely returns to this bad example to prove points. Its like pointing to the invention of the automobile and saying "yes nice, but it doesnt work when you put it in the ocean so its doomed to fail".

I find it interesting that the author does mention constraints, parametrics and the “evolve -> evaluate” stage in the design cycle, but they seemingly dismiss it when it comes to making their arguments. For example “(1) designers define the project’s goals, (2) algorithms produce a range of solutions, and (3) then designers pick the best result” This is wholly wrong and a simplification, which further leads me to believe the author doesnt understand the field, because if they did they would understand that parametrics is a way to make the process iterative, a way to navigate/reduce the possibilities, which they then later go on to describe as one of the main issues with GD.

Author says better algorithms would produce fewer results not more. On what grounds ? If the constraints are narrow a tool might only produce 5 or 6 outputs. If the tool produces too many outputs, you refine the constraints. The goal of GD is to show the designer options which are within a valid scope. If the constraints are wide ranging, parametrics allow the designer to hone in on what they want without worrying about what won’t. Its frustrating to read the author write about algorithms as if they are this complicated black box that just produces outputs and the designer cannot interact with. This is the point of parametrics and constraints.

The author points to GDs absence in other fields as some sort of proof it doesn’t work, but as someone who works in graphic design and previously video game development, I can tell you that adoption is growing for generative tools. Admittedly though, it does require designers to think about design differently, but thats what new tooling is supposed to do. Haven’t Zaha Hadid among others been using parametric tools for years now? Perhaps generative design is not so much doomed to fail in architecture as it is actually just further ahead of other industries.

David Byram

Daniel, Just read you piece on "Generative Design" and completely agree. Being a design engineer over many years from the drafting board to AutoCad and then 3d CAD, when I saw the hype by Autodesk regarding GD, I instantly dismissed it. In the real manufacturing world, there are way to many directions a design can go. Interestingly, there was a piece that came up from Machine Design Magazine that discussed a study done by ASME in conjunction with, wait for it, Autodesk. They "determined" that GD should be required training in colleges, and of course the academics agreed. I replied back to the piece indicating that viewing GD from one software company with a vested interest was not good practice. The piece was entitled "Transform Manufacturing Education to Boost Productivity".

David C Byram

Daniel Davis

Thanks David - it's really valuable to get that perspective from the manufacturing world. And pretty rich to see Autodesk sponsoring a study that suggests their technology should be taught in schools, love their moxy!