Recently I edited out a section from a top-be-published journal article because it meandered off topic and past the word count. Despite the journal editor’s draconian word count, I thought it potentially useful to other people. So here it is, rewritten and free of word counts.

There are 2035 parametric models shared publicly on the Grasshopper forum. I downloaded these models and looked for trends in the way they were structured.

1. Most popular nodes

Unsurprisingly the slider was the most popular node with 11,842 occurrences in the 2035 models. Panel, Group and Scribble come in 2nd, 3rd and 9th place, which is the result of people documenting their models (in the forum people know their model will be read so they put some effort into explaining it). 4th place is occupied by ‘List Item,’ which leads a group of list management nodes - Series, Cull, Graft, List Length, Flatten Tree - dominating the top 30 most popular nodes. It is significant that the most popular modelling operation in Grasshopper should be list management. When teaching Grasshopper I find list management to be the hardest topic to explain, and yet Grasshopper's list management tools are some of the most powerful short of pure scripting. It should be pointed out these results are a little biased in that there are many different types of geometric modelling nodes and while no single node is popular, in aggregate they are popular. Nevertheless the list of most popular nodes should serve as a useful guide for teaching Grasshopper and the customisation of the Grasshopper menus.

The full list of most popular nodes can be downloaded here.

2. Strangely unpopular

The neglected nodes speak volumes for how people use Grasshopper. Falling down the bottom of the popularity list is poor old 'Cluster,' who sits in 159th place. There are a few reasons for this:

- Cluster has only been available in Grasshopper 0.8 while the models in the Grasshopper forum stretch back to version 0.6.

- People are probably more inclined to share small snippets of models on the forum and therefore don't require clusters.

- Clusters was buggy when it was re-released.

Yet, if we only look at the models created in Grasshopper 0.8 and only look at the models that contain more than 26 nodes, only 3.6% have one or more clusters in them :( This means most of the models people are creating in Grasshopper, even the really really really large ones, are totally unstructured, like the example in the next section:

3. Model size

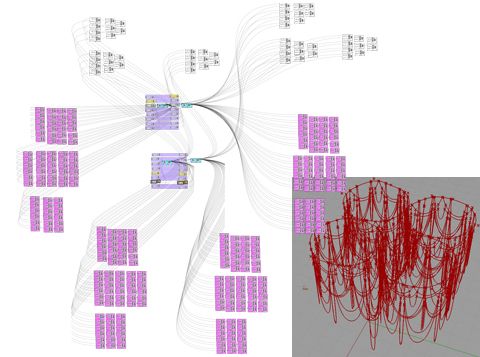

The medium size of a model shared on the forum is 26 nodes, probably lower than what you would expect in practice due to people often sharing just small snippets of models. Yet a couple of models contained over 1000 nodes. The largest model I could find on the Grasshopper forum is a monster by the name of 'hybridB02 (2).ghx' (in this thread) weighing 20mb and containing 2584 nodes. It looks a little bit like this:

hybridB02 (2).ghx is a pretty classic case of copy-paste, and if it gets the job done who cares. But this type of unstructured model could be a huge liability if it ever needs to be edited. Say the original pink box is wrong, you edit it but to propagate the edit through the model you need to delete every instance you copy-pasted and copy-paste in the new version. Or, as we often do, start again.

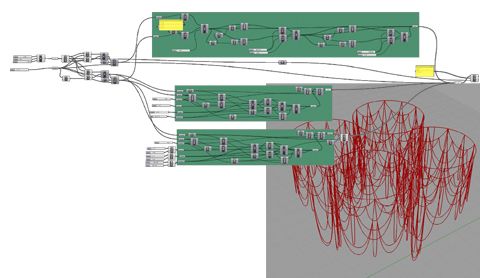

I was curious about what the model would look like refactored and quickly attempted to refactor it myself (see above). One of my first moves was to reduce the dimensionality of the model. There are approximately 500 sliders in the original model, so the model is effectively no longer parametric since moving the 500 sliders would be just as difficult as moving 500 points on an explicit model by hand. Often a formula is used to reduce dimensionality of a parametric model, however in this case I used rotational symmetry to simplify things. This might have made the geometry too neat for some tastes but you could always use a formula to tweak each rotated instance. The resulting model has 126 nodes and 20 sliders, making exploration of the design space far more viable - although the model is by no means perfect.

Refactoring the model introduced quite a few of the list management nodes. This is both the reason they are popular (they are really useful) and the reason managing lists is problematic (people starting out in Grasshopper are unlikely to use them). In completing this research I had planned to make one more list of my own, a list of popular combinations of nodes but this will likely have to wait for another paper and a more friendly editor. It looks like my friend the cluster will have to wait a while longer too, as I have quite subconsciously left him out of the refactored model.

And if you are in, or near, Melbourne in November, we are going to be hosting a week long computational design workshop with Hugh Whitehead - Director of the Specialist Modelling Group at Fosters. Find out more at http://designingthedynamic.com/

Jim Steel

Hi Daniel,

Are you doing other kinds of measurements? I'd be interested in having a chat about some more software engineering-oriented measurements I've been thinking about if you want to shoot me an email.

Jim.

Daniel

Hi Jim,

- Just sent you an email.

I haven't extracted any other measurements at this stage. I was thinking of looking at graph coupling, Cyclomatic complexity, and clustering of common nodes.

If anyone else has suggestions of potential measurements (or wants the data to make their own), please feel free to add a comment or send an email.

Andrew Heumann

fascinating stuff! The list of most popular components alone is really interesting, I am going to have a serious look at it before I teach my next GH seminar.

Thanks for sharing your work!

Andy Payne

Thanks for sharing the data. Really interesting results.

John H

Nice piece Daniel.

Whilst admittedly being a liability in the face of change, the unstructured model (somewhat ironically) actually offers the most design freedom because it is effectively just a normal CAD model as you say with no predetermined dependencies.

By constraining yourself more and more (by adding more and more relationships/edges), you are essentially becoming further locked into where you have got to. The structured model i>also becomes a liability' should any drastic changes to the design be required (this paper by Holzer et al. shows such an example in practice: http://multi-science.metapress.com/content/d670305x0703160n/).

I personally believe we have gone too far and need to think about making parametric modelling software more adaptive (topologically speaking) in the light of unpredictable changes, not just sliders tweaking variables but graph structures that are much looser, somewhere in-between. How we go about that is another matter altogether - perhaps graphs are the wrong vehicle altogether.

Anyway, very interesting. Thanks for posting this, would make a great paper regardless of word count... I'd read it!

Daniel

Hi John,

Thank you for passing on Dominik's paper (I have never seen it despite seeing Dominik often in Melbourne) it is really pertinent to my current work.

I agree flexibility is more than just sliders and that the real challenge with a parametric model is being able to easily modify the schema (or collection of relationships and constraints). One example I look to is computer programmers and when they talk about structure they are really talking about organising your code so it is reusable, and therefore hopefully able to be recycled in the project when a major change comes through. In the post I was indirectly referring to a paper I wrote on this topic (http://www.nzarchitecture.com/page.php?id=39). With CITIA - the software Dominik used - it is difficult to change the schema, partly because relationships are implicitly hidden within the tree, and partly because if you change the structure of something like a powercopy you normally need to write a script to re-instantiate the powercopy throughout the model. In my opinion it is not so much that constraints constrain you, it is that the software we build parametric models in (whether it is Grasshopper or CATIA or something else) does not facilitate elegant transitions of the schema organisation.

So I guess that is a roundabout way of telling you I agree we need to think about making parametric modelling software more adaptive. I would be surprised if graph-based-parametric-models / visual-scripting is the best way to achieve this. My hunch is that we can learn something from computer programmers, but I suspect this is just an interim measure until someone discovers a better way all together.

Daniel